What Security Housing Units Look Like

The number of women in prison has increased by 646 percent between 1980 and 2010. Women are traditionally the backbone of communities and homes, but if an increasing number of women are being incarcerated what happens to the community and their families?

Though the U.S. teen birth rate has dropped to record lows, South L.A.'s teen birth rate continues to stay well above the national average and remains the highest in the county.

Los Ryderz is a non-profit bike club that rides with 40 at-risk youth in the area of Watts.

It was lonely, quiet, and constricting in the 8 by 10 foot security housing unit 4B where Armando R. Morales spent nearly 23 hours a day in isolation at Corcoran State Prison.

He entered the prison system at age 16, and for the last eight years of his life spent his term in a security housing unit, often referred to by advocacy groups as solitary confinement.

Morales was 29 years old when he hanged himself by a shoe lace and a blue blanket in his unit on August 28, 2012.

Armando Robert Morales, known as "Bobby" by his family, was one of 32 inmates in a California prison who killed himself in 2012.

He was housed in the "SHU" -- a place where inmates are 33 percent more likely to commit suicide than inmates in regular cells, according to Dr. Raymond Patterson in a federal report.

Prisoners in the SHU are 2 percent of California prisons' population, but make up 42 percent of suicides overall, according to a 2012 report by Amnesty International, a global human rights group.

Stories like Morales' are one of the reasons that California Families Against Solitary Confinement are pushing the California prisons to change the way inmates in segregation are treated.

"The psychology trauma from a place like that -- I can only imagine how horrifying must be," said Peggy Replogle, Morales' aunt. "But Bobby always managed to stay positive and I never understood that."

Lawyers from New York to California filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of 10 prisoners at Pelican Bay State Prison against Gov. Jerry Brown and California prisons in 2011.

The suit aims to change how prisoners in the SHU are treated, stating that it goes against prisoners' 8th amendment rights to keep them in isolation because it constitutes cruel and unusual punishment.

The Department of Corrections countered the accusation that security housing units are solitary confinement, saying the conditions in the California prison system far exceed basic constitutional rights.

"To say that these inmates are devoid of any human contact couldn’t be further from the truth," said Terry Thornton, spokeswoman for California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. "They interact with staff, they are allowed visits – and some are in double cells."

The lawsuit also demands decades-long terms in solitary be abolished, and putting an end to the debriefing system, which groups allege forces prisoners to "snitch" on fellow gang members.

Thornton said the advocacy groups are pushing their agenda without looking at facts, and the idea that the prison officials force inmates to "snitch" is absurd.

"In the old program, if they wanted to leave their gangs, then we ask for intel," Thornton said. "But we don’t force anyone to debrief."

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation asserted it has already implemented changes since class action lawsuits and inmate hunger strikes.

Out of 237 inmate cases, Thornton said 90 were released to the general inmate population with the implementation of a new program that has changed the way inmates enter and leave the SHU.

Before it was "intel" based, meaning information could land an inmate in the SHU.

Now, the program is behavior based, and committing crimes will earn a term in the SHU.

But California Families Against Solitary Confinement , along with other advocacy groups, said the changes CDCR has made are not enough. They demand contact visits, not visits where families view the inmates through Plexiglas.

"This means that prisoners may not even hug or hold hands with visiting family members, children, or other loved ones," lawyers wrote in the complaint.

For one hour a day, Morales was given the opportunity to exercise outside in a caged area.

Morales described the space to his aunt, Replogle, who called it comparable to a "dog run."

"It's a wired cage where he was able to pace around – and he only received one hour a week for exercise, and showers every three days," Replogle said.

No phone calls are allowed, and meals are delivered to prisoners through a small slot at the front of the cell.

A small metal sink and toilet are in the space, along with a bed.

Dr. Terry Kupers, a clinical psychologist, said having little to no human contact in a windowless cell is detrimental to the human psyche, and backed CFASC in its pursuit for change.

"They're idol, they have nothing to do and they have anxiety," Kupers said. "They suffer from panic attacks, and anger. When you have inmates in solitary all suffering from the same feeling of dread, that means something."

Morales was a validated associate of the Mexican Mafia — also known as “Le Eme,” — and was interrogated after a raid was conducted on his girlfriend’s house that revealed letters from prison where gang members were identified, according to Stevens and prison records. It was months before Morales' death.

"Anyone reading the letters I got from him would not have thought he was going to kill himself," Stevens said.

In 2004, Morales was convicted of assault on a prison guard with a deadly weapon, a third strike that added 28 years to his existing 37-year sentence, according to prison records.

He participated in a widely publicized hunger strike, during which he lost 30 pounds. Inmates across California went for over two weeks without food in protest to the conditions in security housing units and the debriefing process."We are not even asking them to leave their gangs," Thornton said. "We’re just asking them to stop engaging in gang activity – to stop running drugs, to stop taking orders from someone to kill people."

Thornton also said she disagrees with the advocacy groups' characterization of a security unit's conditions, saying the meals are "better than other meals she has had" and California prisoners receive some of the best medical treatment in the nation.

"There isn’t a day that goes by that there aren't fights, or assaults," Thornton said. "We need to protect our staff, and protect other inmates."

Morales was 21 when he entered a security housing unit.

He spent his time in prison earning a GED, and eventually a paralegal degree to help other inmates with legal advice for their cases.

Morales wasn't always a troublemaker, his sister Stevens said.

Morales played little league baseball, and aspired to be a pilot as a child. Morales' mother attempted to "bribe" him into behaving by paying for pilot lessons around the age of 14, but by this time he was already exposed to gang culture.

According to Stevens, Morales' stepfather abused him, throwing him against walls when he misbehaved.

"Our stepfather was perfect before they got married," Stevens said. "But afterward he was like a different person."

Morales had been in and out of juvenile hall since he was 13 years old after becoming involved in the notorious Grape Street Crips gang in Watts.

Though Morales lived in Apple Valley, his friends and fellow gang members would pick him up and drive him to Watts to do "bad things," Stevens said.

Morales was sent to a boys' home in San Diego to shape up, but soon returned home and fell back into his old group of friends.

At age 16, Morales entered the prison system for brandishing a box-cutting razor at an undercover officer when the officer accused him of shoplifting, according to his sister.

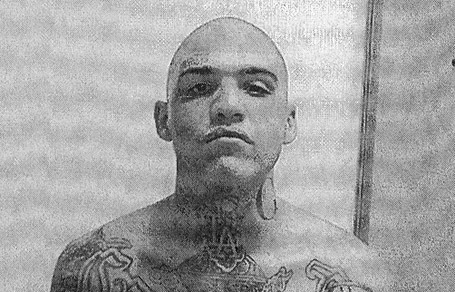

While serving time as a general population inmate, fellow inmates inked gang-related tattoos all over his body, including a sizeable "WATTS" tattoo across his abdomen, and "LA" across his throat.

He also had his mother's name tattooed on the side of his neck, and his sister April's name on his wrist.

His sister said it was all a part of appearing tough in prison.

"He always wanted to be strong, and never let my mother visit him because he would break down and show weakness," Stevens said.

Morales entered the SHU in 2004 after assaulting a guard.

"He beat him within an inch of his life," Stevens said.

Morales spent nearly half of his life in prison, where he learned fluent Spanish and an Aztec language. He also passed the time by drawing, including one illustration of a demon clutching a naked woman on a bed of skulls. Other illustrations depicted a Latino male, decked in tattoos similar to Morales', standing amid giant letters that spell out "LIFE."

In letters to Replogle, Morales mentioned that she needn't worry about her job as a teacher at Jordan Downs Middle School in Watts, his former gang territory.

"I told him I didn’t want to know anything more, and that I could take care of myself," Repogle said. "I could tell when I walked by gang members in Watts that there was this weird aura of respect – like they received word that if Bobby's aunt got hurt, there would be hell to pay."

Morales communicated with his family via mail every month, up until 2012 – that's when Morales missed sending an important card. His sister, Stevens, said he sent a card in the mail for her birthday on April 28 every year, except for 2012.

The entire year of 2012, Morales didn’t keep contact with his family. Then Stevens and Morales' mother received the shock of their lives – they were told that Morales hung himself in his cell in August.

"I still don’t believe he committed suicide," Stevens said.

In fact, no one in the family does. Stevens and Replogle allege they try to get information out of the prison system, and get the run-around. They also said his autopsy report wasn't filed until weeks after his death.

After Morales' death, the prison sent a box of his belongings to the family. The contents included letters from his girlfriend, sweat pants. Among the rest: A pair of sneakers without laces.